Yikes! Scientists have been studying plastic-based environmental pollution by looking at microplastic particles. A concerning study of microscopic plastic particles at the sub-micron level shows bottled water is more polluted than tap water.

A new study published in the peer-reviewed journal "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences" provides an unprecedented look at the mysterious world of plastic pollution. A team of researchers at Columbia University developed a new optical imaging technology, which they used for rapid analysis of nanoplastic particles in bottled water.

The imaging solution allowed scientists to profile individual "nanoplastic" particles. Nanoplastics measure less than one micrometer or less than one-seventieth the width of a human hair. The Columbia team discovered an average liter of bottled water contains an astounding amount of plastic – about 240,000 sub-micron particles. This number is far greater than a 2018 study showing the average bottle held 325 micro-particles.

The Washington Post notes that research on plastic pollution during the past several years shows signs of microplastic in every corner of the planet. Microscopic pieces of plastic were identified on the deepest seabeds in Antarctica, in soil samples, in wildlife, and even in the human placenta.

The biggest issue with plastic materials is that they are constantly shedding. Like human skin, plastic containers slough off invisible particles into the food and water we eat and drink, and these microplastics are essentially becoming part of both the human body and the environment.

The dangers microplastics pose to human health are still under investigation. According to Wei Min, a Columbia chemistry professor and one of the study's authors, nanoplastic particles will eventually be more dangerous than whatever harm microplastics are causing now.

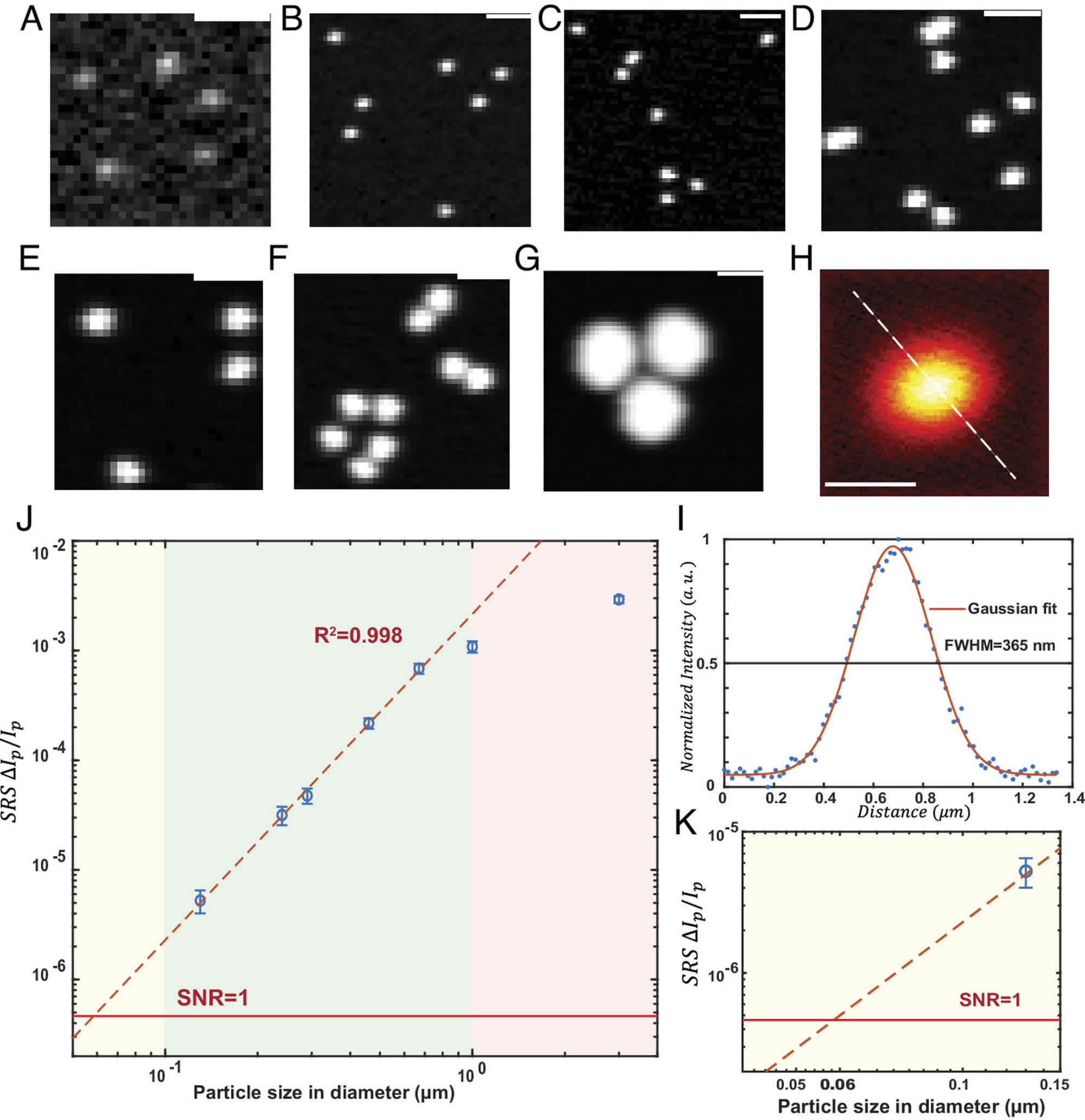

Previously developed methods to identify nanoplastics weren't precise enough to provide an accurate number of particles. The new technique employs two lasers aimed at a sample to observe and record the resonance of different molecules in the water. The researchers leveraged machine learning algorithms to identify seven different types of plastic molecules from a sample of three types of bottled water.

While researchers debate a potential link between microplastics in water and human health, this unprecedented study on nanoplastic detection should at least provide new evidence to fuel the scientific debate and an additional tool for further analysis. Mounting discoveries suggest that the fragmentation of plastic polymer does not stop at the micron level. Instead, it continues to form nanoplastic particles in quantities that are "orders of magnitude higher."

. We can't change the past, but going forward we can make personal decisions to mitigate risks of exposure imo.

. We can't change the past, but going forward we can make personal decisions to mitigate risks of exposure imo.