Editor's take: Intel faces three sequential problems: fix manufacturing, start designing competitive products again, and win some customers for IFS (Intel Foundry Services). Then they have to keep all that going. Not impossible, just very challenging.

We've been receiving many inquiries lately about the current state of Intel. Since this topic seems to be of great fascination for much of the semiconductor world, we thought it might help to put our thoughts down here.

Intel is presently facing a series of sequential problems. Sequential in the sense that each issue must be resolved before the next can be effectively tackled. The company is working on all of them, but they are interdependent in such a way to confound the company's prospects until each one is resolved.

Editor's Note:

Guest author Jonathan Goldberg is the founder of D2D Advisory, a multi-functional consulting firm. Jonathan has developed growth strategies and alliances for companies in the mobile, networking, gaming, and software industries.

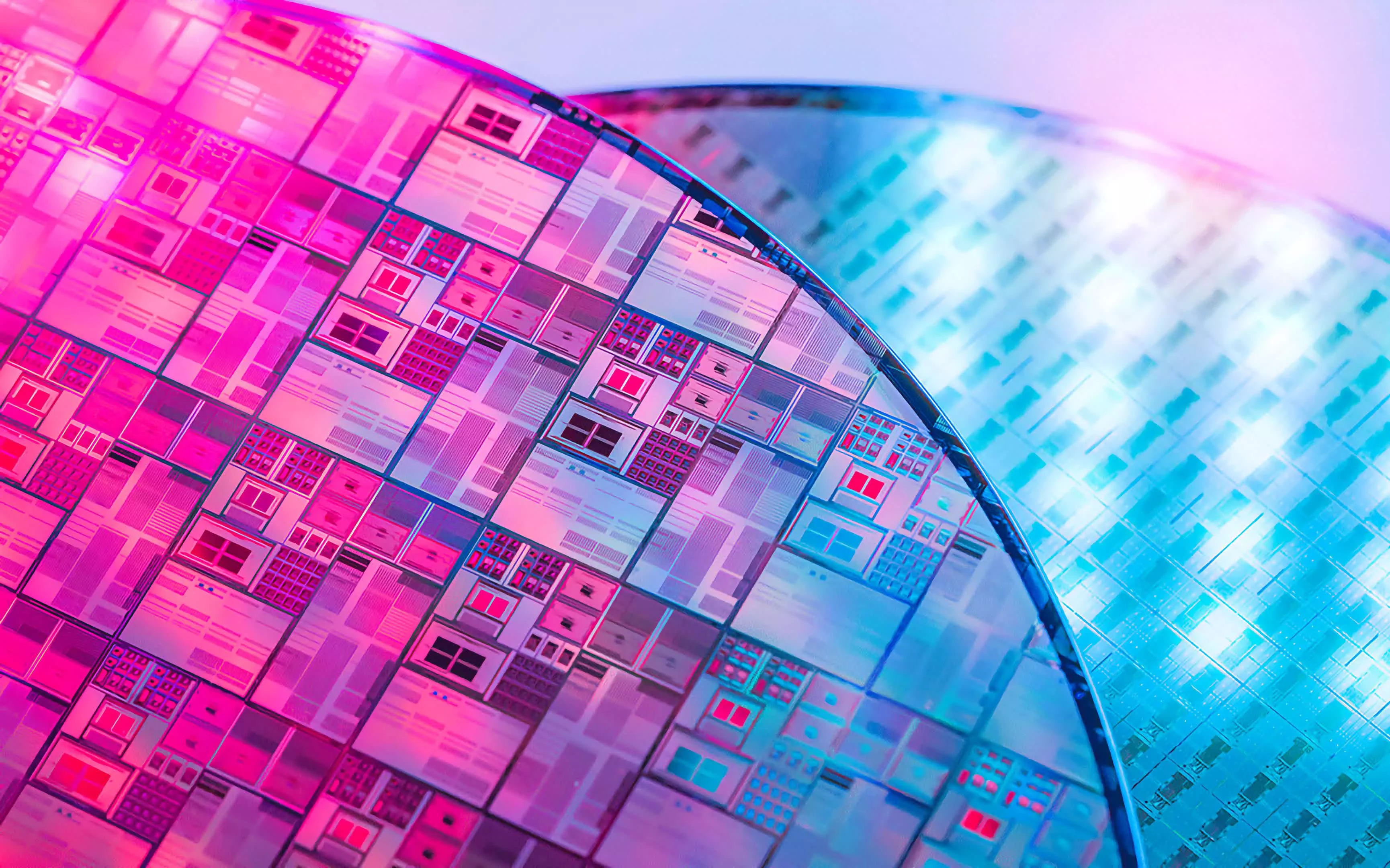

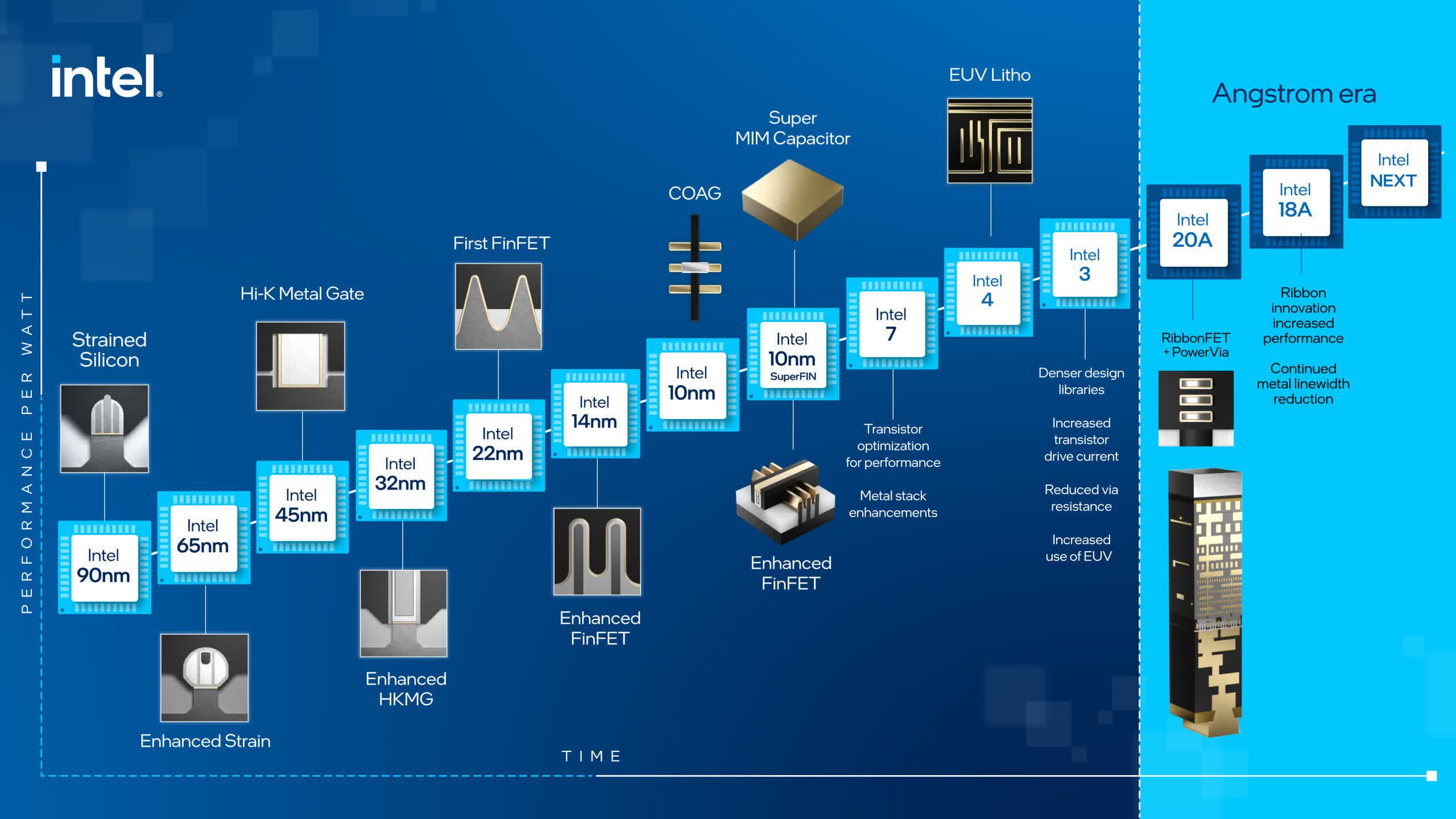

The first problem Intel must overcome is its manufacturing process. The company is structured around its IDM model (Integrated Device Manufacturing), with internally controlled fabs. While they have outsourced some of their production to TSMC, approximately 70% of their revenue still originates from their own fabs.

The company fell off the Moore's Law path several years ago, and is now racing to catch up. The ambitious goal of advancing five nodes in four years has become the company's official slogan. This issue is of existential importance to Intel, and failure to address it could spell a bleak future for the company.

As far as we can tell from the outside, they are on track to reach that goal, but more than a year remains before these advancements can be fully implemented. Achieving this is incredibly challenging, but if we had to make a prediction today, we believe they can reach a level that will allow their products to regain competitiveness, though outpacing TSMC in the near term seems less likely.

This brings us to the second problem. Assuming Intel's manufacturing process achieves an acceptable level, they will then face competition from their products. Here they face a litany of difficulties. At the top of that list is AMD, which has been executing like the proverbial machine. AMD's latest CPU portfolio looks very compelling to customers.

They have introduced significant innovations in the CPU market, such as their chiplet architecture and associated packaging. AMD argues that their current products are more performant and offer a better Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) than Intel. This gap will likely widen as Intel continues to address its manufacturing issues, a process that probably won't conclude until late 2024 at the earliest.

Furthermore, the market is undergoing a shift. In data centers, customers are moving away from CPU-centric systems towards heterogeneous computing involving CPUs, GPUs, and accelerators. While Intel offers GPUs and AI accelerators, their impact in the market is modest, to say the least. It seems Intel is exerting so much effort to survive that they aren't updating their roadmap to adapt to these new realities. We're being generous here, as many believe the situation is far more dire.

Put simply, when Intel entered its current funk in the middle of the last decade, they had one CPU competitor, but today they face a dozen. A revived Intel can face off all these challenges. They still have a solid position in the PC market and long-established relationships with the whole ecosystem, but they need products which can stand on their own.

And then we reach the third problem – they have to keep all of this going. That means investing heavily in advancing their manufacturing process. Even if they can achieve some version of 5 nodes in 4 years, they have to keep moving beyond that. The economics of Moore's Law are punishing, only companies with massive revenues can sustain the pace of investment required.

The third challenge is the ongoing commitment to improvement. This involves heavily investing in advancing their manufacturing process. Even if they can achieve their target of five nodes in four years, they must continue to evolve beyond that. The harsh reality of Moore's Law is that only companies with substantial revenues can sustain the necessary pace of investment.

This problem is deepened by the fact that Intel's fabs produce so much less than TSMC. In order for Intel to sustain the R&D pace it needs to fill up its fab with more than just their own products. This is a matter of compounding. Part of the reason TSMC has become the leader in semis manufacturing is that they produce so much volume, which means they learn faster than everyone else, a critical component of all of this.

So, in order for Intel to sustain itself, in the future it has to build Intel Foundry Services (IFS) into a bona fide foundry competitor. Customers will only consider IFS if they believe it can compete with TSMC. This is why we see Intel's challenges as sequential. Despite persistent rumors of fabless companies considering IFS, we don't foresee this becoming substantial until Intel proves its manufacturing process is both competitive and sustainable. We believe IFS won't significantly contribute to revenue until the end of the decade.

Fundamentally, Intel's greatest challenge is cultural. The company must acknowledge the changing world and adapt accordingly. Over the years, Intel created immense blind spots by focusing inward excessively, losing sight of its diminished stature compared to its glory days. Therefore, it was somewhat disconcerting to hear Intel claim during their recent analyst update that IFS is "The world's second-largest foundry," a calculation that included their internal products. This is akin to taking your hot older sibling to prom. Technically it's true, but it doesn't convey the image they think it does.

While this might seem insurmountable, a few factors favor the company. They have immense internal talent, which appears to be both committed and invigorated. Additionally, they don't need to excel in every aspect. For manufacturing, they don't need to surpass TSMC, merely get close enough so the process no longer undermines their products. They don't need to be the second-largest foundry in the world (excluding their own product), they just need to secure a few fabs' worth of external customers.

Tough, but not impossible.