Intel put out some solid earnings results last month. We don't need to rehash those here; instead, instead want to focus on one particular aspect of their numbers – their long term gross margin guidance. In the latest quarter they reported 42.5% gross margins, but critically, they restated their goal for someday achieving gross margins in the 60% range.

Six months ago, most people, including us, dismissed that goal as fanciful at best. But now, we all have to at least consider the possibility, however slim, that they might actually achieve it. Particularly, understanding how Intel is restructuring internally in preparation for launching Intel Foundry Services (IFS) as a third-party foundry for semiconductor designers is crucial.

Editor's Note:

Guest author Jonathan Goldberg is the founder of D2D Advisory, a multi-functional consulting firm. Jonathan has developed growth strategies and alliances for companies in the mobile, networking, gaming, and software industries.

Earlier this year, Intel announced changes to its internal accounting methods. Under the new system, Intel's product division and fab operations will each have their separate P&L and will interact with each other on an arm's-length basis. Previously, the two divisions blended their costs, with operations costs hidden within product margins.

While this might seem like a trivial accounting adjustment – after all, the company will still report consolidated gross margins, which remain unchanged – this subtle shift will significantly impact internal incentives. Our core thesis on Intel is that their most significant challenge lies in changing their internal culture, making this 'small' change potentially very impactful.

Our core thesis on Intel is that their most significant challenge lies in changing their internal culture, making this 'small' change potentially very impactful.

After the earnings report, we had the opportunity to speak with management about their results and dug into how they plan to achieve their long-term goal. A key takeaway from this conversation was the management's assertion that they are implementing many 'easy' internal steps to improve gross margins.

Some measures are straightforward, like benchmarking fab operations costs against industry peers. Others sound simpler than they are – like charging the product side for rush orders or 'hot lots'. An obvious question arises: if these are all 'low-hanging fruits', why weren't they already implemented? The answer is that these changes are not as easy as they seem.

Imagine you are an Intel salesperson responsible for a hyperscaler client – a major provider of cloud computing, networking, or data storage – whose data centers are major consumers of Intel chips. The customer is about to make a big purchase decision between Intel and AMD CPUs for a potential $1 billion order. If you win, you get the Cadillac and a giant bonus. AMD launched a new chip earlier in the year, but the Intel product is just coming out.

The client wants to test both options in a 1,000 CPU system under real workloads. Your product is in short supply, but using the previous generation of Intel CPUs would likely hand the win to AMD. So, you request a rush order of 1,000 parts from the operations team.

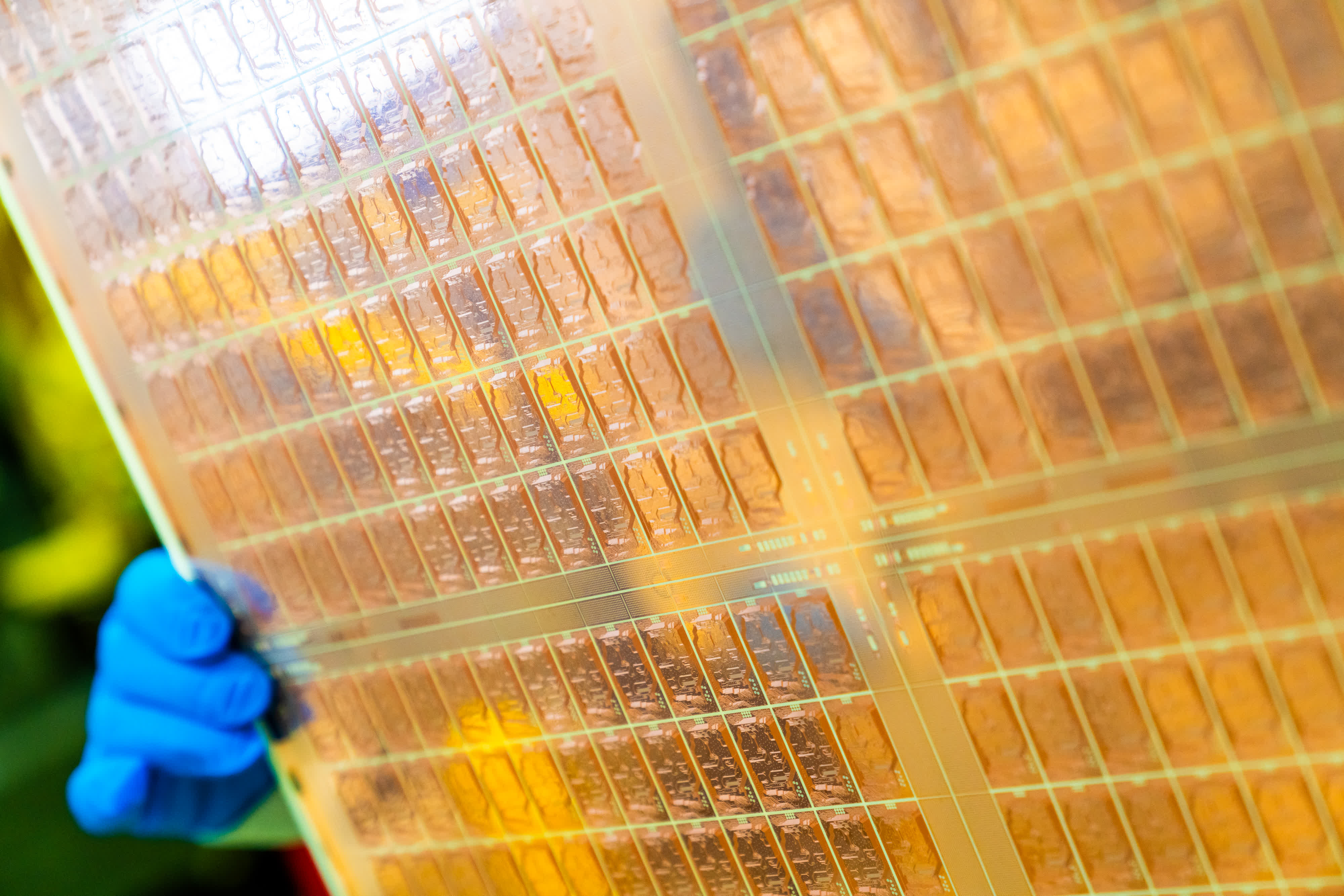

The operations people are reluctant to do this because the product is new, yields are low, so they will have to produce double the amount of wafers to get 1,000 good chips. Moreover, the customer wants a specific SKU or version of the chip, but the operations team is already set to produce a different SKU. To get those 1,000 parts will require them to shut down the fab for a few hours to re-tool, produce your chips, and then shut down again to re-tool for the original plan.

When the fab costs $30 billion to build, a half day of downtime probably costs something like $10 million in deprecation. Under the old model, you did not care, because you know you can win that $1 billion order, and all those charges will become rounding error for the sale.

Under the new model, you now have to bear the full brunt of those charges. Let's say this order is taking place close to the end of the year, so you will have to take the charge on this year's numbers, and will not get the purchase order until the next year. With your P&L in that shape, you will not get the steak knives, you will probably get fired, and someone else will get the benefit of that purchase order next year. But if you do not place the rush order you will likely lose the deal entirely. What would you do in this situation?

Of course, this is a highly simplified scenario, but it aptly illustrates the profound cultural shift about to take place within Intel. Intel's previous practices, embedded into its business model and sales strategies, provided a significant advantage over competitors. Without this tool – or perhaps crutch – the sales team will need to lean much more on product performance alone.

This shift is likely to impact their market share and revenue outlook in complex ways. As our hypothetical situation demonstrates, much will depend on individual decision-making, group dynamics, and management culture. Will the salesperson's boss adopt a long-term perspective? Will the operations team maintain any level of flexibility? How will senior management handle disputes? And will management consent to a one-time exception, which then becomes the norm, effectively nullifying the purpose of the change?

Accounting can be boring, but sometimes it leads to very interesting developments.